I know, I know. It’s already been a few days after Thanksgiving, but I’m still recovering from a food coma that just won’t seem to go away. At least I can still spare myself of the Black Friday experience, an Armageddon over the last parking space too small and wool sweater that won’t fit. That said, after the psychedelic trips resulting from copious amounts of turkey, leftovers, and American consumer capitalism, it’s hard to turn back to Skid Row. After all, gluttony and excess don’t necessarily resonate well with the estimated 74,000 homeless individuals in L.A. County.

But in the spirit of the holiday season (which hopefully for all Americans is a time of giving back to those in need), I’ve turned to the county’s new plan to address homelessness in Los Angeles. According to this recent article published in the Los Angeles Daily News, this past Tuesday L.A. County Supervisors approved Project 50, a plan that aims to identify the 50 most vulnerable individuals on Skid Row and move them into supportive housing.

Modeled after projects already underway in New York City and elsewhere, Project 50 hopes to save the lives of “those most likely to die on the streets,” said this recent LA Times article. These are also the same individuals who have run up the biggest bills in the county, costing tax payers millions of dollars in cycling through emergency medical rooms, shelters and jails.

At the same time, these individuals are considered “anchors” or people of authority among the chronically homeless – classified as one-third of the county’s 74,000 homeless people who have lived on the streets for a year or more and have disabilities such as AIDS or mental illness. As a “block captain” on Skid Row, other men and women look up to these people, learning their street smarts them and gaining street cred.

In turn, officials expect that these 50 individuals will inspire others to seek help.

In turn, officials expect that these 50 individuals will inspire others to seek help.

“In the social hierarchy that exists on the streets, these anchors are at the top of the food chain,” said Board Chairman Zev Yaroslavsky. “What's happened in other parts of the country is when the anchors are brought in off the streets, a good percentage of the other people who are marginally homeless access services, too. They kind of follow the lead of the anchors.”

The county has set an estimated budget of $800,000 for services to the fifty people. One homeless individual can cost from $40,000 to $100,000 per year for shelter, incarceration and emergency room care. But in terms of supportive, permanent housing, these costs range from $14,000 to $25,000, said Gary Blasi, a UCLA law professor who has studied homelessness. The City’s Skid Row Housing Trust is set to provide apartment housing for these 50 individuals by February.

Experts say that placing the chronically homeless in permanent housing with ready access to social services is much more effective than providing them with temporary shelter. The chronically homeless are “fragile in terms of both physical and psychological health,” said Phillip Mangano, executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on homelessness. “Delivering the treatment and other services that they need is more effectively done when a person is in a stable location.”

Blasi adds that 85 percent of homeless individuals who live in supportive housing stay off the streets.

Critics charge that the program targets too small of a group of people in what is largely acknowledged as the nation’s largest homeless population. And to that, county officials say that they plan to eventually expand the program across Skid Row and elsewhere, pointing to the strategy in New York City, known as Street to Home, initiated by Common Ground. The Times Square project helped house more than 90% of the homeless people living in that part of Manhattan. Common Ground is currently expanding this model in areas of Brooklyn and Queens.

The expectation that the project will eventually include more people is debatable. And if more individuals are included, will the numbers make enough of a difference in the future? Some homelessness advocates agree, saying that a slow, but steady approach is better than nothing at all.

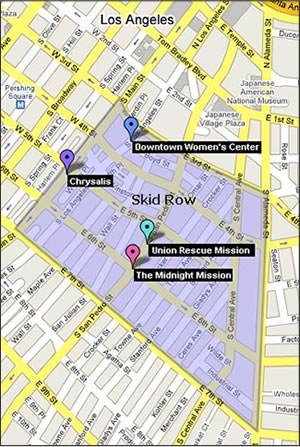

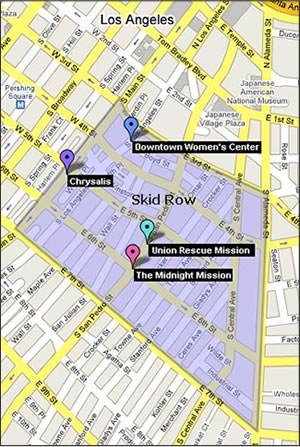

But is Project 50 the right model for Los Angeles (apparently with the worst homelessness problem in the nation)? Skid Row alone is population to an estimated, but varying 8,000 homeless people, according to this recent article in GOOD magazine. And with that, the faces of Skid Row are changing. Yes, there are the Vietnam veterans, drug dealers, coke addicts, and criminals. But within this city within a city, there are also families living out of cars and single mothers moving their children in and out of the infamous Ford Hotel. And we can’t forget the faces of recent immigrants, unsuccessful white-collar workers, divorced ex-husbands, failed fathers, and the list goes on.

These faces are not only changing, but they are moving – moving around in a county that is approximately 4,060 square miles. As multi-million dollar lofts in downtown continue to be renovated within a spitting distance from Skid Row, luxury BMW’s and Mercedes vehicles drive along San Julian St. – a true testament to the ever-increasing gap between the rich and poor in this city. Moreover, these groups are having to make home elsewhere…and elsewhere again, with current transient trends moving toward Boyle Heights.

Today, young professionals don’t even have to think twice about when and where to find their next, new luxury apartment. Nearby, the homeless residents of Skid Row and L.A. County have been waiting for an eternity for a roof over their head. And with Project 50 underway, it seems that for the remaining 73,950 homeless, they’ll just have to wait some more.

Additional Sources:

(New York Times) Some Respite, if Little Cheer, for Skid Row Homeless

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/31/us/31skidrow.html

In turn, officials expect that these 50 individuals will inspire others to seek help.

In turn, officials expect that these 50 individuals will inspire others to seek help.