Speaking of politicians capitalizing on the fears and anxieties of the public, this LA Times article identifies illegal immigration as the most pressing issue within the GOP. That’s right, it even surpasses healthcare and the war in

Wednesday, December 12, 2007

Jumping the bandwagon

Thursday, December 6, 2007

Campaign ads reaching an all new low

Tancredo, “Tough on Terror”? Right. More like, let’s group together what have seemingly become America’s biggest fears: terrorism and the invasion of illegal immigrants deemed as the other. The result is an uber alarm against the two, yet more so a wake-up call to the latter. Literally warning Americans “before it’s too late,” Tancredo is obviously positioned as the answer to it all.

What the ad does in actuality, though, is stereotype all of the 12 million undocumented immigrants estimated by TIME magazine – I’m sorry, that’s 20 million aliens according to the senator – by immediately associating them with the imminent desire to blow up American malls. Moreover, Tancredo targets not only Islamic terrorists (and people of this faith in general), but makes a sweeping reference to Latino and Asian immigrants with the “20 million aliens already taking our jobs.”

What I take issue with then – other than this sensationalist approach of galvanizing political support – is the fact that people like Tancredo often do not ground their assertions in facts. Rather they largely base them off of the public’s trends of anxiety and fear, which is then reinforced by these same politicians in a never-ending cycle.

Thus, it comes at no surprise that such negligence of the truth is drawn into another segment of the national debate on immigration: the costs of undocumented immigrants for the American taxpayer versus the contributions that they make to the American economy. In these recent articles from both the LA and NY Times, researchers have found that in some cases, the contributions far outweigh the costs in healthcare, education and other social services. Adding to that, such expenses are far much less than they have typically been made out to be.

In the LA Times article, the focus of illegal immigrants’ use of public services is on healthcare. According to the Times, UCLA researchers have found that illegal immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries are 50 percent less likely than U.S.-born Latinos to use hospital emergency rooms in California. In this study published in the journal Archives of Internal Medicine, researchers confirmed that immigrants are indeed less likely to be insured and seek routine and preventive care. The reasons? Not because this generation of illegal immigrants is younger and healthier than the overall population, but rather they do not seek medical treatment out of fear of leaving a paper trail.

Even Alexander N. Ortega, the lead author of the study, agrees in the reluctance of some politicians to acknowledge fact. “The current policy discourse that undocumented immigrants are a burden on the public because they overuse public services is not borne out with data, for either primary care or emergency department care,” said Ortega, also an associate professor at UCLA’s School of Public Health.

In the NY Times article, immigrants, both legal and illegal, are attributed to one-fourth the economic output for New York State. From a statewide immigrant population of 21 percent, contributions to the state GDP were $229 billion in 2005, as stated in the independent study “Working for a Better Life.” The estimates are that 16 percent of the 4.1 million statewide immigrants are residing there illegally.

Again, case in point, “We just felt like there was such a deep misunderstanding about who immigrants were that the political discourse often got far afield from any factual basis of what’s really going on here,” stated David D. Kallick, the principal author of the study.

Put that in your backpack and blow it up, Tancredo.

And since I’ve already jumped back to the ad, I still must give credit to the senator’s brilliant use of the ticking time bomb, images of terrorist attacks abroad, and the suspicious-looking, could be your next-door neighbor, hooded culprit. That said, Tancredo does an excellent job of capitalizing on the fears and suspicions of immigrant-weary Americans. At the same time, I’m just tired of hearing all of the b.s. while people eat it up like it’s candy.

Additional Links and Sources:

(LA Times) Few migrants, much opposition

Saturday, December 1, 2007

A new battle takes to the field

South Central Farmers acquire 85 acres of new farmland in Buttonwillow, California*

*Note: The following information has yet to be published in the media, though its source is confirmed by longtime SCF organizer and advocate, Sarah Nolan.

A year and four months after the forcible eviction from their 14-acre community garden on 41st and Alameda Streets, the South Central Farmers (SCF) now have a new place to call home – well, maybe not home, exactly. In October 2007, the South Central Farmers Health and Education Fund (SCHEF) secured a loan from an anonymous non-profit organization, allowing SCHEF to purchase 85 acres of land in Buttonwillow, California. As such, the farmers maintain that they have only been displaced, not defeated.

“We stood up for the needs of the community and we will continue to develop the work that was done at the South Central Farm,” stated Rufina Juarez, SCHEF president. But this isn’t the first time that the farmers have brought in fresh produce following the eviction. Since summer 2006, SCF has been farming on smaller community gardens throughout Los Angeles and on leased land in collaboration with other agricultural cooperatives in Fresno and Bakersfield.

Yet this new farmland, just east of Bakersfield, resembles little of the 14-acre urban oasis that had served as the foundation of SCF. Without the picturesque setting of massive walnut trees and burgeoning flowers collectively halting South Central’s typically blighted landscape, row upon row of crops frame this farmland. As part of the Central Valley, Buttonwillow is situated in the region that sustains California’s most productive agricultural efforts.

Still, many things remain the same. Dotted by hunched-over wives and husbands or fathers and daughters, the new farm is still the site of toddlers running through the furrows. And as the farmers finish churning the earth, planting and watering seeds, weeding tiny sprouts, and harvesting crops, they must package all of the produce, driving it along Interstate 5 and back into South Central by Sunday. Once here, the fresh, organic produce is sold by SCF at a monthly “Tianguis” (Meso-American marketplace), in which music, dancing and other cultural events also take place.

And the food does not stop here. Nearly a ton of produce – including Swiss chard, radishes, squash, lima beans, broccoli, cauliflower, corn and other crops – is distributed and sold in farmers markets across Los Angeles. All of the excess produce is then donated to Catholic Charities, Food Not Bombs, food banks in Azusa and other local, non-profit organizations.

As such, the South Central Farmers embody all that is grassroots LA. Their continued srength and solidarity despite eviction, displacement and repeated setbacks is exactly what this city needs and thrives on - even if it is the City working against them for most of the time. With the mayor waning in support for SCF since his 2005 election into office and Councilwoman Jan Perry (District No. 9) who has always kept close relationships with city developers for political support, SCF has learned that they cannot depend on these same elected officials to maintain their empty promises.

Moreover, as the lengthy appeals process over the original 14-acre farm continues in the courts, SCF cannot and has not waited to address the needs of the community. While SCF refuses to give up on this land, continuously striving to bring local farming back to South Central, this goal is just one part of a larger objective now. The destruction of the original farm and current displacement of the farmers has not stopped SCF from pursuing its greater mission of bringing healthy food and nutritional consciousness into the city’s most impoverished and neglected communities. According to Sarah Nolan, longtime SCF advocate and organizer, “The fight is not over, it’s just a different struggle.”

Sarah Nolan

SCHEF

Phone: (888) SCFARM-1

Fax: (302) 370-0612

(USA Today) Dozens arrested at L.A. community garden

http://www.usatoday.com/life/people/2006-06-13-urban-garden_x.htm?POE=LIFISVA

(L.A. CityBeat) Tezozomoc

http://www.lacitybeat.com/article.php?id=1955&IssueNum=98

(BBC News) Actress Hannah in garden protest

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/5078404.stm

(Washington Post) Farmers vow to prevent garden demolition

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/06/14/AR2006061402132.html

Saturday, November 24, 2007

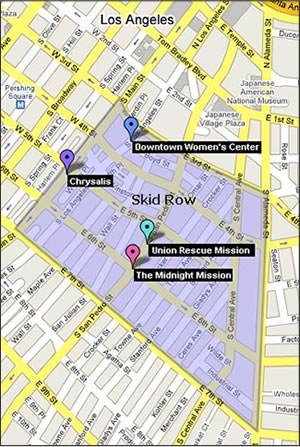

The vulnerability index on Skid Row

I know, I know. It’s already been a few days after Thanksgiving, but I’m still recovering from a food coma that just won’t seem to go away. At least I can still spare myself of the Black Friday experience, an Armageddon over the last parking space too small and wool sweater that won’t fit. That said, after the psychedelic trips resulting from copious amounts of turkey, leftovers, and American consumer capitalism, it’s hard to turn back to Skid Row. After all, gluttony and excess don’t necessarily resonate well with the estimated 74,000 homeless individuals in

In turn, officials expect that these 50 individuals will inspire others to seek help.

In turn, officials expect that these 50 individuals will inspire others to seek help.

“In the social hierarchy that exists on the streets, these anchors are at the top of the food chain,” said Board Chairman Zev Yaroslavsky. “What's happened in other parts of the country is when the anchors are brought in off the streets, a good percentage of the other people who are marginally homeless access services, too. They kind of follow the lead of the anchors.”

The county has set an estimated budget of $800,000 for services to the fifty people. One homeless individual can cost from $40,000 to $100,000 per year for shelter, incarceration and emergency room care. But in terms of supportive, permanent housing, these costs range from $14,000 to $25,000, said Gary Blasi, a UCLA law professor who has studied homelessness. The City’s Skid Row Housing Trust is set to provide apartment housing for these 50 individuals by February.

Experts say that placing the chronically homeless in permanent housing with ready access to social services is much more effective than providing them with temporary shelter. The chronically homeless are “fragile in terms of both physical and psychological health,” said Phillip Mangano, executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on homelessness. “Delivering the treatment and other services that they need is more effectively done when a person is in a stable location.”

Blasi adds that 85 percent of homeless individuals who live in supportive housing stay off the streets.

The expectation that the project will eventually include more people is debatable. And if more individuals are included, will the numbers make enough of a difference in the future? Some homelessness advocates agree, saying that a slow, but steady approach is better than nothing at all.

But is Project 50 the right model for

Today, young professionals don’t even have to think twice about when and where to find their next, new luxury apartment. Nearby, the homeless residents of Skid Row and

Additional Sources:

(New York Times) Some Respite, if Little Cheer, for Skid Row Homeless

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/31/us/31skidrow.html

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Gang series: Part I

For leaders of the Mexican Mafia, “stone walls do not a prison make, nor iron bars a cage.” According to this recent LA Times article, much of the gang violence in

Under orders from imprisoned leaders of the Mexican Mafia (La Eme), Florencia 13 (F 13s) gang members allegedly attempted to “cleanse” their neighborhood of rival black gangs. But so much for getting the ‘bad’ guys – or other bad guys, I should say. It turns out that the numerous assaults and murders “extended to innocent citizens who ended up being shot simply because of the color of their skin,” said U.S. Attorney Thomas P. O’Brien.

But there were some exceptions to this rule – that is, when money is involved. Latino gangs allegedly sold large amounts of drugs and sometimes guns to blacks, including Crips gang members. At any rate, near the end of October, 102 people – mostly members of Florencia 13, based in Huntington Park and the Florence-Firestone neighborhood – were charged with illegal drug and weapons sales, conspiracy and racketeering.

According to this article in CityBeat, news of these charges comes as a sense of vindication for some and a bitter pill to swallow for others. Many black and Latino community activists have struggled for years to get law enforcement and city leaders to admit that many of the racially-charged murders in the area are intrinsically gang-related – particularly comprising pieces of the Mexican Mafia’s larger plot to cleanse their neighborhoods of the black population. And while law enforcement and prosecutors have admitted before that some Latino gangs have attacked innocent victims based on race, this is the first time that the Justice Department has publicly disclosed the Mexican Mafia’s racist agenda – one that is also against prison blacks and includes known collaborations with the Aryan Brotherhood.

For Florencia 13, one of the largest street gangs in the city, racially-charged murders operate as one function in a complexity of organized crime. Members have been ordered to tax prostitutes, ice cream vendors, taxi operators and dealers of fake green cards. At the same time, networks of shooters, gunrunners and drug dealers rule the streets. And as we’ve just witnessed, organized crime is still just as organized behind bars.

In April 2007, Villaraigosa issued his “Gang Reduction Strategy” in response to the recent increase in gang-related crime (14% from 2006), despite the city’s decline in overall crime for the fifth straight year. In the report, the mayor called for a “comprehensive, coordinated, and sustained” approach to combating gangs. While devoting more resources toward arrest and prosecution of gang members, Villaraigosa stressed that prevention, intervention and re-entry are key tools of the trade.

Funny, this model sounds a lot like what Father Gregory Boyle has been doing in

But this recent article in GOOD magazine highlights Chief Bratton’s announcement in January that gangs will be met by an “unprecedented collaboration” of resources from the FBI, LAPD and other local agencies. The article also hints that the city’s official plan is to “pursue the most notorious gangs and hope for a trickle-down effect to curb the violence.”

However, with all this emphasis on suppression, it comes at no surprise why gang violence is still a viable option for even younger and younger crowds in

What they’re fleeing from is what the mayor identifies as the most problematic of social conditions – poverty, a failing education system, domestic abuse, negative parenting, child abuse and neglect, and the tolerance of the gang culture. (Of course, as if we didn’t already know this from before). And in addition to calling a war on gangs, Villaraigosa also calls on a war on social ills.

Saturday, November 3, 2007

America, the land of selective milk and honey

If it’s one thing that Americans are good at, it’s crushing dreams.

Saturday, October 27, 2007

To protect and serve

Maintenance of law and order is a prerequisite to the enjoyment of freedom in our society. Law enforcement is a critical responsibility of government, and effective enforcement requires mutual respect and understanding between a law enforcement agency and the residents of the community which it serves.

-McCone Commission, Violence in the City: An End or a Beginning?

The fact is that the LAPD is not just a police department extolling a mission to “protect and serve” without much to show for it. Rather the LAPD is a manifestation of a history marked by police brutality, racism and scandal, embodying an organizational culture that values police authority and independence above the rule of law.

Wednesday, October 24, 2007

8th Annual Festival de la Gente - Día de los muertos

Because there's more to Halloween than dressing up as a...well, you get the point.

Because there's more to Halloween than dressing up as a...well, you get the point.Entonces, celebra el día de los muertos.

Good music, good eats, good people.

On the streets of Los Angeles at the historic 6th Street Bridge.

Saturday, October 27, 2007

11 am-10pm

Sunday, October 28, 2007

11am-8pm

For more info check out the website at:

http://www.festivaldelagente.org/

Thursday, October 11, 2007

Father G and the Homeboys

Saturday, October 6, 2007

Events for this weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

October 4, 2007

Contact: Tezozomoc

818-892-5248

South Central Farmers Tianguis

Celebrating the Continuing Resistance of Indigenous People Around the World

WHAT:

1) Bringing Food to the Hood- Organic produce

2) Workshops and Food Demonstrations

3) Music and Entertainment

WHEN:

Date -- Sunday, October 7, 2007

Time -- 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

(Also…Please Save the Date for our Dia De Los Muertos Celebration on Sunday, November 4th)

WHERE:

On 41st Street (between Long Beach and Alameda)

The SCFHEF Community Center & Gallery

1702 E. 41st Street

Los Angeles , CA 90058

(Metro: Exit Blue Line Vernon Station and walk four blocks North)

WHY:

The South Central Farmers stand in solidarity with the continuing resistance of indigenous people around the world. Specifically we recognize the up coming Continental Indigenous Encuentro in Mexico, Anti-Columbus Day, and the March Against Police Brutality.

WHO:

- Traditional Danza Azteca-Chichimeca & Music

- Children's Workshops and Stories

- Holistic Care & Products

- South Central Farmers Cooking Demo

- And More!

Massive sweep deports hundreds...

...more to come on this issue. But for now take a look at this LA Times story that was also featured on NPR-KCRW's "Which Way L.A."

...more to come on this issue. But for now take a look at this LA Times story that was also featured on NPR-KCRW's "Which Way L.A."

Friday, October 5, 2007

When faith hits the streets in L.A.

Who knew that the Los Angeles Times had a Religion section online? At any rate, in this article, “Religion as a force for good,” opinion writer Ian Buruma expands on the notion that “it is often the faithful who are inspired to do great things.” As seen from the Burmese rebellion, Buruma also draws on this religious inspiration from other faiths and their historic impacts on the international front. At the same time though, Buruma touches on the public intellectual’s tendency to downgrade religion, linking it to “backwardness” and the principle reason for all of society’s ills. Thus, Buruma cites, “It has become fashionable in certain smart circles to regard atheism as a sign of superior education, of highly evolved civilization, of enlightenment.”

Similarly, Stephen Mack illustrates this idea in his article “Wicked Paradox: The Cleric as the Public Intellectual.” Focusing on the makings of American democracy Mack states, “Nearly every significant movement for social reform in American history was either started or nurtured in the church.” But while Mack cites national movements, from labor reform and women’s suffrage to prison reform and Civil Rights, Buruma goes abroad. Thus, he gives credit to Catholicism for “People Power” in the

So Buruma says it best in that the “Moral power of religious faith does not need a supernatural explanation,” nor does it have to be in a supernatural being, “Its strength is belief itself, in a moral order that defies secular or indeed religious dictators.”

Sunday, September 30, 2007

Saturday, September 29, 2007

Americans as religionphobes with the public intellectual caught in between

So from where religion and politics meet, what typically results among liberals, the democratic left and even public intellectuals is a “secular bigotry,” as Mack so deems it. Believed among these groups is the acceptance of religion in its influence on your moral values (this of course, has to be positive). But once you bring those religious beliefs into the political forum, uh oh, wait. No, you must stop there and abandon your faith, grounding public arguments solely in reason and evidence. Thus, in an attempt to promote a “diverse democracy” in which a common political language exists, theology cannot speak as people of faith are demanded to “be other than themselves and act publicly as if their faith is of no real consequence.”

Interestingly enough, where does one draw the line between this secular bigotry and fear of religion? Just watch the film "Jesus Camp" or simply read the title of Christopher Hitchens’ recent best-seller, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. And while works such as those from Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins link religion to backwardness, I’m beginning to sense a hint of religious phobia here. At the same time though, how can Americans not play into this fear? In an era where the word jihad is immediately associated with suicide bombers and the Los Angeles Archdiocese is coughing up $764 million for victims of sexual abuse, there exists the pressing need for public intellectuals to take the high road (or safer one for that matter) and distance themselves as much as possible from religion.

In a recent TIME article by Michael Kinsley, current Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney is cited for trying to play the J.F.K. card among voters. In seemingly opting out of his Mormon faith, he tries to persuade the American public in that his religious beliefs are of “his own private affair.” But what Kinsley demonstrates is that “these days presidential candidates are required to wear their religion on their sleeve.” And if religion is so central to their lives and moral values, it cannot be limited to just a private prayer/ personal reflection time before bed – as is the case for many presidential candidates on the left and right.

As Kinsley states, we need to know in what ways a candidate’s religious doctrine forbids or requires action and how she or he must deal with these religious improbabilities. Must we refer back to the times when Bush had said that God led him to his Iraq policy? We deserve to know the extent of which a candidate believes in the doctrines and perspectives of their faith, as this reveals much about their character. After all, a candidate’s “leap of faith” may be admirable or even essential in voters’ minds. On the other hand, some may find it offensive when a candidate’s religious beliefs – and actions based on such values – fail to agree with their own.

But what are Romney and other presidential candidates (Obama, Clinton, McCain, etc.) really doing? When it comes down to it, other than standing on deep religious convictions, candidates seem to be playing on the public’s fear toward religion, or apprehension at the very least. In the case of Romney, Kinsley sums it up rather nicely in that:

It will be amusing if Romney is done in by a fear of his religious values because, as near as we can tell, he has no values of any sort that he wouldn’t abandon if they become a burden. But in politics, you are who you pretend to be.So while candidates seem to be playing on both sides of the fence, the current race to the White House continues to feed into the public’s phobia of religion. Continuing with this fear, of course, is the wicked paradox of the religious public intellectual.

Events to check out for this weekend

For those of you who who are kept up late at night because of the racket that those damn LAPD helicopters make, this may be an event for you. But if this one may be too intense, you might want to try the Los Angeles inauguration for the 2007 Swerve Festival:

Swerve Festival is a new annual festival dedicated to celebrating West Coast creative culture and its community inspired by art, film, music and action sports. The three-day celebration will be held in Los Angeles to bring together a dynamic group of innovators and thinkers and to spotlight some of the most exciting work to come out of these creative disciplines.

Wednesday, September 19, 2007

Over walls and beyond borders: Perceptions and immigrant identities in Los Angeles

At the time of the riots, television screens across the country lit up with the heavy blows that Reginald Denny suffered, as he was dragged out of his cab, kicked and spat upon. In this depiction, Denny, a white truck driver, served as the antithesis to the Rodney King beating that also graced the television screens just one year before. But on that same corner where Denny’s assault had occurred, at least 30 other individuals had been dragged from their cars and beaten. Of these cases, a Mexican couple and their one-year-old child were struck with rocks and bottles; a Japanese man, having been mistaken for Korean was stripped and bloodied; and a Guatemalan man, after being knocked unconscious by a car stereo, had motor oil poured down his throat (Sánchez).

In essence, the Los Angeles riots were the epitome of racialized nativism beyond the black/white racial paradigm. And while this nativism extends into the current political and social setting of Los Angeles, its existence in the 1992 uprising still stems from “an intense opposition to an internal minority on the ground of its foreign (ie. “un-American”) connections” (Sánchez). In this racial and political discourse, however, it is important to distinguish nativism from racism. Following John Higham’s model in Strangers in the Land, racism can result in “unfavorable reactions” toward the personal and cultural traits and traditions of others. These reactions, however, are not necessarily nativist until they have been integrated with a “hostile and fearful” character (Higham).

In his article “Face the Nation: Race, Immigration, and the Rise of Nativism in Late Twentieth Century America,” George J. Sánchez contends that this rise of nativism in Los Angeles is directed toward contemporary non-European immigrants, both legal and illegal, in addition to the generations that follow them. But to wholly understand this xenophobia in the context of Los Angeles today, it is obligatory to trace back to the nation’s earlier experiences with immigration. Thus, in “A Sense of Place: The Politics of Immigration and Its Immigrants,” Kevin Keogan compares such experiences in Los Angeles and New York, two opposing spheres of urban immigrant politics. In this assessment, Keogan identifies the early formations of Los Angeles’ nativist traditions. Ultimately, this begins with identity.

Among Irish, Italians, Jews and other European groups immigrating to New York in the later 19th and earlier 20th centuries, a collective struggle for material wealth and acceptance resulted in a common immigrant identity. Represented through salient landmarks such as Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, this identity transitioned over to later immigrants, mostly from Latin America, the Caribbean and Asia. As a result, years of this continuous and changing flow in immigration have fostered an “immigrant origin mythology” within the New York area. Recognized as the foundation of New York City, immigrants here are emboldened by a specific, positive narrative that upholds their historic place in the community. This mythology, therefore, translates into a collective “immigrant as us” identity (Keogan).

Within the past three decades, however, Los Angeles has taken on a “postutopian tone” as a result of large-scale immigration from Asia, Mexico, Central America, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and North Africa. In “California Dreaming: Proposition 187 and the Cultural Psychology of Racial and Ethnic Exclusion,” Marcelo M. Suárez-Orozco points out that the romantic fantasies and bootstrap models from previous centuries no longer resonate as strongly in immigrant discourse. Instead, this influx of non-European immigrants has transformed Los Angeles into the new “third world metropolis,” as stated by James H. Johnson Jr. in “Immigration Reform and the Browning of America: Tensions, Conflicts and Community Instability in Metropolitan Los Angeles.” And within this transformation, the negative connotations run rampant. In a setting where people of color comprise two-thirds of the metropolitan population, anger and anxieties continue to grow.

In this era’s unique xenophobic environment, recent immigrants are racially identifiable, making them “easily categorized by race into the American psyche” (Sánchez). From here, Johnson recognizes this phenomenon as the steady, increasing fear of the “browning of America.” In this fear stirs a growing intolerance, molded by the perception of an open-door immigration policy in which the nation is unable to stem the tide of foreign invaders. As a result, for most newly-arrived groups in Los Angeles, immigrants are more susceptible to being labeled and treated as a “threat” before anything else.

And as always with immigrant discourse, massive numbers games ensue. Largely centered on what can be measured in terms of the costs and benefits of this phenomenon, how much new immigrants use in social services is often evaluated against what these groups “pay” in local, state, and federal taxes (Suárez-Orozco). But with respect to the volatile formation of immigrant identities, numbers are practically insufficient. What is tangible in this explanation of xenophobia culminates in California’s Proposition 187. Within the passing of this initiative – just two years after the riots – Los Angeles once again reinforced its nativist traditions.

Under the name “Save Our State,” this 1994 ballot initiative gained the support of Californians, with a 59%-41% overall margin. Essentially antiforeign, the initiative sought to punish illegal immigrants by denying them access to social services, non-emergency healthcare, and education for the children of illegal immigrants. Additionally, public agencies were required to report suspected illegal immigrants to state and federal authorities (Suárez-Orozco). But aside from the logistics of the initiative, what is even more disturbingly poignant is the language found in the proposition’s description presented to California voters:

Proposition 187 will be the first giant stride in ultimately ending the illegal alien invasion. It has been estimated that illegal aliens are costing taxpayers in excess of 5 billion dollars a year. While our citizens and legal residents go wanting, those who choose to enter our country illegally get royal treatment at the expense of the California taxpayer (State of California).Thus, with such ferocity, this language encompasses Los Angeles’ xenophobic core.

Historically “defensive in spirit,” this racialized nativism has undoubtedly set the trend for an exclusionary political climate in Los Angeles today (Higham). From a basic antipathy toward non-English languages to the embodiment of xenophobia in California’s Proposition 187, these exclusionary means describe Southern California’s profound sense and fear of the “decline of the American nation” (Sánchez). Moreover, Los Angeles continues to be haunted by what Suárez-Orozco deems a climate of “frustration and malaise.” Immigrants are not just feared and resented, but they are fabricated and fictionalized in front of a larger backdrop in which the greater problems that plague this city are displayed.

Thus, why immigrants face such hostility is more than just a matter of color, racism and fear. Easily dehumanized, recent immigrants become categorized as the “other,” especially when economic hardship and frustrations ensue. This categorization, however, stems from a need by dominant groups to single out recent immigrants. In this new “transnational malaise,” these groups become the focus of powerful anxieties when both the state and city have failed to solve its most pressing domestic issues: poverty, inequality and justice (Suárez-Orozco).

As “domestic aliens,” recent immigrants are identified with the abuse of social services, the refusal to assimilate, and the breeding of crime in the urban landscape (Suárez-Orozco). Panic and hysteria surrounds these already vulnerable groups, making it easier for “native” Angelenos to render them as scapegoats in times of economic stagnation and political instability. Unfortunately in this rendering, a sense of humanity is lost among them.

What many already know is that most immigrants essentially want to be reunited with their families, seeking better work conditions and wages at the same time. But despite this reality, resentment and anger from “native” Angelenos still follows them. As recent immigrants and minorities continue to grow to become the majority in numbers, they are viewed as a social class that is too self-involved and “out-of-touch.” As the economy declines, they are connected to the “disappearance of jobs” and draining of resources. As education standards fall short, they are responsible for an education system that cannot teach. And as crime rates increase, they are viewed as the cause for a justice system that is already broken (Suárez-Orozco).

To surmise immigration and racialized nativism in Los Angeles, Nathan Glazer says it best in that “economics in general can give no large answer to what the immigrant policy of the nation should be.” After all, figures and statistics can only go so far in explaining how people think, feel, and act in respect with one another. Ultimately, it is always easier to take in everything at first glance, especially by seeing in what we believe.

Perception is everything – be it one-sided, conservative, incorrect etc. But when perception plays into identity, especially group identities, much more is at risk here. For recent immigrants in Los Angeles, perceptions centered on hatred, anxiety and panic have robbed them of the immigrant mythology from centuries past. Though a bit romanticized, at least this collective identity was more accepting, fostering, and encouraging than what newer immigrant groups have been confined to today.

Culminating in the 1992 uprising, perceptions of an invading immigrant class enveloped Los Angeles in a climate of fear, frustration, and anger. At the expense of this racialized nativism, 52 lives were lost, 2,383 people were injured, and over $1 billion of damage was done to residences and businesses (Sánchez). Again, 15 years later, Los Angeles finds itself in another tumultuous and tense political environment. From a failing housing market linked to increased gentrification, to the recent May Day riots that epitomized both police brutality and police distrust, Los Angeles is still plagued by a xenophobic character from which it can’t seem to shake free.

According to Suárez-Orozco, I guess the better question to ask now is if “We can’t deal with ourselves; how are we to deal with others?” But at the very least, in order to better understand – if not “solve” – the larger issue of immigration, it may be more beneficial to look inward as opposed to outward. After all, perceptions and identities from all sides can be misleading.

http://zb5lh7ed7a.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=jstor:jstor&genre=article&issn=0048-7511&eissn=1080-6628&volume=28&pages=327-339&spage=327&epage=339&atitle=Instead%20Of%20a%20Sequel%2c%20or%20How%20I%20Lost%20My%20Subject&date=2000-06&aulast=Higham&issue=2

Johnson, Jr., James H., Walter C. Farell, and Chandra Guinn. “Immigration Reform and the Browning of America: Tensions, Conflicts and Community Instability in Metropolitan Los Angeles.” International Migration Review. 31.4. (1997): pp. 1055-1095. <http://www.jstor.org/view/01979183/di009796/00p0315c/0>

Keogan, Kevin. A Sense of Place: The Politics of Immigration and the Symbolic Construction of Identity in Southern California and the New York Metropolitan Area.” Sociological Forum. 17.2 (2002): pp. 223-253. <http://www.jstor.org/view/08848971/sp030001/03x0005e/0>

Sánchez, George J. “Face the Nation: Race, Immigration, and the Rise of Nativism in Late Twentieth Century America.” International Migration Review Special Issue: Immigrant Adaptation and Native-Born Responses in the Making of Americans. 31.4 (1997): 1009-1030. <http://www.jstor.org/view/01979183/di009796/00p0313a/0>

Suárez-Orozco, Marcelo M. “California Dreaming: Proposition 187 and the Cultural Psychology of Racial and Ethnic Exclusion.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 27.2 (1996): pp. 151-167. <http://www.jstor.org/view/01617761/sp050101/04x0225q/0>

Thursday, September 13, 2007

Because you can never get enough shopping in LA

For up to $70 million, you too can get a brand new 500,000-square-foot mall and a Lowe’s home improvement store. But wait, there’s more! Today’s package – brought to you by the lovely developers of Midtown Crossing – also includes a wonderful, three-story parking lot. Call within the next 15 minutes and you can get the limited edition Starbucks and Jamba Juice gift set for free!!!

Okay, so this article in the LA Times didn’t exactly use an announcement like this for the new 10-acre retail development that is to be built in Mid-City within the next 16 months. But at the current rate of revival projects that the city is undergoing (Spring St., downtown, USC, and so on) Los Angeles may as well be called “The City of Dislocation.” So a 20 second spot on a late-night infomercial could be somewhat feasible in this sweeping “wave of gentrification.”

Centered on the crossing of San Vicente and Pico, Mid-City has long been a neglected neighborhood after the 1965 riots and 1992 uprising left the area in economic decay. The boarded-up Sears is just one of the artifacts that serve as a testament to the region’s plight. Darnell Hunt, director of African American Studies at UCLA, called the development “momentous” since retailers have always been reluctant to build there.

But while the gentrification has mixed reviews from residents, local business owners, and city officials, Midtown Crossing is already set to bring in the largest and first major project that Mid-City has ever seen. Drawings for the mall already show similarities to the Grove. Great. Good luck finding parking and fending off the hordes at the after-Thanksgiving Day sales.

But in a neighborhood that has been struggling for the past 40 years and is still predominantly working-class, how willing are big-city developers to assess, let alone provide for a community’s needs? Other than increased foot traffic and cash flow (which go hand-in-hand with car congestion), what about current living wages and local businesses? Will the community’s residents be able to reap the rewards? And at what point does “new mall” mean “move out” for the neighborhood’s poor?

An older article from USA Today offers an interesting take on gentrification and how the poor are not really “pushed out.” The 2005 article, however, doesn’t specifically include Los Angeles as an example. LA Weekly published a more recent article on this topic, explaining how Angelenos, poor and rich alike, are no exception to the Ellis Act – or the condominium uprisings and spawn of $4 latte/gelato shops.

I, myself, enjoy a small Salvadoran pupuseria over a Baja Fresh or Chipotle any day.